Four hundred years ago, during the heyday of the London plague, the English government had realised that an educated populace outweighed the authoritarian need to monopolise public information. Thus, the London Bill of Mortality was born in July 1603: the first public health media artefact that provided a detailed listing of plague deaths and sites of contagion.

Much like the printed artefact in 17th-century London, social media has become the public platform of choice for the COVID-19 crisis – the first pandemic of the digital age.

In the last few weeks, digital natives and netizens have thronged social media platforms. And in such large numbers, one might add, that the media influencer’s pipe dream, of breaking the internet, has seemed a genuine possibility. Internet service providers in the UK have seen double-digit increases in traffic amid the coronavirus lockdown, and streaming services from Netflix to Disney+ are cutting bandwidth usage to prevent network congestion.

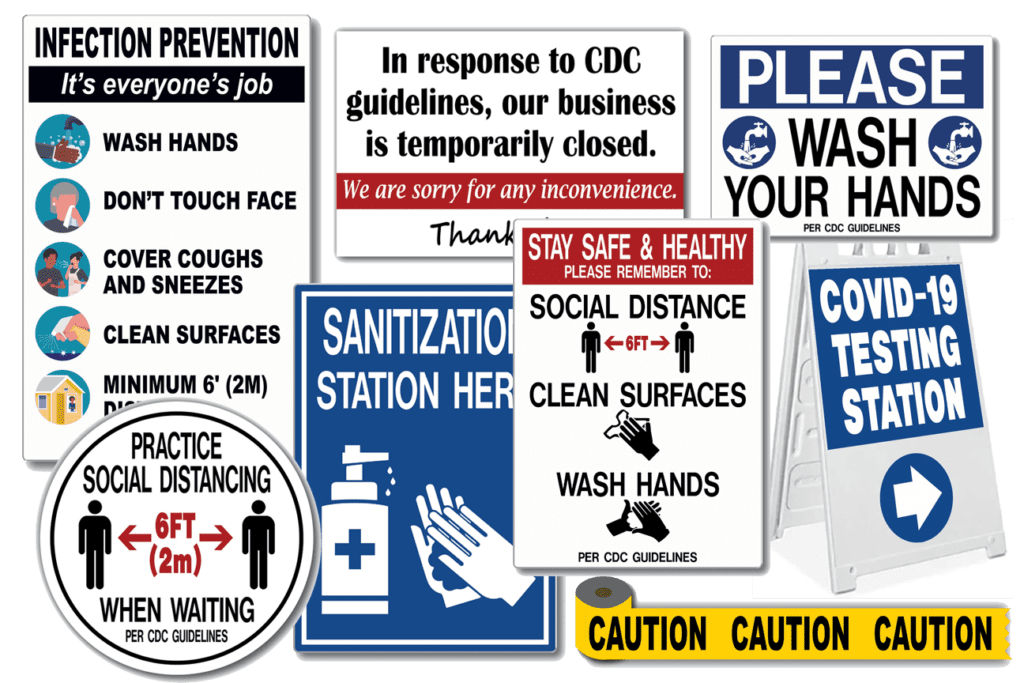

In the US, there were nearly 20 million mentions of coronavirus-related terms on social media, within hours of the World Health Organisation declaring the COVID-19 crisis a pandemic on March 11. In the following days, the trending hashtag-based campaign #safehandschallenge (also started by the WHO) has seen a host of global celebrities – from Selena Gomez to Deepika Padukone – educate the public on the mundane act of hand-washing through carefully curated social media performances. However, the issues of access and privilege that plague social media platforms, particularly in the Indian context, beg the question: Can spectacular social media platforms handle the quotidian coronavirus crisis?

It is often said that the history of diseases is the history of human civilisation. And the foundation of human civilisation is also the mundanity of manual contact. Everyday and necessary, but often unseen, transactions of money or goods between strangers have driven human progress for millennia. But in exceptional times (like our current crisis of contagion) we have looked for egalitarian and non-human surrogates of information: a (new) media. The search for credible yet democratic media paradigms, however, has rarely been smooth.

In the last century, the movement for democratising mass media was galvanised during the May 1968 unrest in France. These protests led the French situationist Guy Debord to claim in The Society of the Spectacle – a book that has since been translated into nearly a dozen languages – that mass media thrives within an alienated and consumerist fantasy.

Now sitting in the 21st century, a call for discarding all networked mass media may seem delusional. But it is worth revisiting how the shift from traditional mass media to new (social) media has led an era where, to rephrase Andy Warhol, everyone will be world-famous for 60 seconds. An attention economy has catalysed this transition, from low-key chat rooms to 60-second digital extravaganzas. The result: truth and legitimacy most often become collateral damage in these networked spectacles.

Network lessons from quotidian corona

“[T]he quotidian is what is humble…what is taken for granted . . . undated and (apparently) insignificant.”

∼ Henri Lefebvre, Everyday Life in the Modern World

The current COVID-19 crisis is by contrast a quotidian disaster – an anti-spectacle. The coronavirus is indifferent about humanity. The perpetrator of this disaster does not identify victims by class, creed, religion or sexuality. It remains invisible to the naked eye but is not miraculous, magical or sacred. The virus is not circulated through hidden test tubes smuggled by secret organisations. Instead, the virus gains enormous latitude through ordinary manual contact with humans and material objects.

Resistance against the coronavirus involves mundane practices like social distancing and washing hands which (without discounting the economic and social privileges involved) society normally categorises as ordinary and banal. Recording the effects of the virus does not involve drone-based targeting of veiled enemy assets or covert sting operations. Chronicling its effects is also unremarkable, laborious and time consuming. It requires a recording of the everyday life cycle of affected victims: a slow and painstaking process by any count.

In other words, the COVID-19 crisis is not a disaster that can be delivered in byte-sized snippets to a globe-trotting populace that constantly puts a premium on shock and titillation.

India, although a recent entrant within the global hierarchy of producing and consuming digital media spectacles, is fast catching up (Indians consume over 11 GB data every month). Nielsen, the market research firm, reports that social media conversations in India around COVID-19 have seen a massive surge of 50x between January and March 2020.

Social media enthusiasts will argue that spectacular campaigns are needed in a country like India, where only two out of 10 poor households use soap. However, questions remain if current social media frameworks can address caste and class privileges, which are key factors behind such dismal personal hygiene statistics amongst underprivileged communities. Such disparities are only augmented by the fact that out of 560 million people in India who have access to the web, only 294 million users use social media. Coupled with such inequality in access, a recent report in The Wire suggests, the COVID-19 crisis has seen a deluge of deliberate misinformation on Indian digital platforms, which has contributed to further marginalisation of at-risk-minorities.

A decade ago, Tim Berners Lee, the creator of the world wide web, had lamented in his prescient article ‘Long Live the Web‘ that the insulating nature of social networking sites is increasingly preventing the democratisation of the web:

“Large social-networking sites are walling off information posted by their users from the rest of the Web. Wireless Internet providers are being tempted to slow traffic to sites with which they have not made deals. Governments—totalitarian and democratic alike—are monitoring people’s online habits, endangering important human rights. If we, the Web’s users, allow these and other trends to proceed unchecked, the Web could be broken into fragmented islands.”

Berners-Lee’s claims are contested by pragmatists like Alexander Galloway, professor of media, culture and communication at New York University, who point out that this fragmentation is inevitable since the very foundation of the internet – its protocols – is based in the principles of control and not freedom. In fact as this era of surveillance capitalism shows regularly, shutting down a country’s internet is far less difficult (and increasingly more common) than one would imagine.

So, does the answer lie in moving away from social media in this crisis? Absolutely not.

The COVID-19 crisis is an opportunity for a re-engagement with everyday threats that are most often beyond the realm of social media spectacles: public health lapses, climate change issues, unequal technological frameworks and discriminatory social, political and legal decisions to name a few. It is an opportune moment to recognise that social media is not just meant to be a “network without a cause”. Indeed, the social media we want should work for everyone and it is up to us to make that happen. And contrary to expectations, such possibilities do exist.

For example, UNESCO’s ‘Horyu’ is “a social network for social good [that takes] a humanistic approach to technology to promote social good through quality content and meaningful interaction”. There are also GnuSocial, OpenSource-SocialNetwork and the Diaspora Foundation, which allow you to create your own social networks with a particular focus on access, freedom and privacy. They offer tangible alternatives to social media platforms, where your data is centrally located and regularly monetised.

Closer home, organisations like Janastu that provide free open-source software solutions and support to non-profits and NGOs as well as the Internet Freedom Foundation, which has championed net neutrality and individual privacy in India (including a recent representation on COVID-19 quarantine lists that are being circulated on social media) show us how in today’s world of networked capitalism, we can be distant without being socially isolated.

The COVID-19 crisis has given us a unique chance to be empathetic ethnographers of the everyday. To amplify the voices of migrant workers who work in our homes and offices, to understand the labour of medical care givers who toil on without expectations, and to acknowledge the polyphony of ordinary subaltern voices who often remain hidden under the spectacular glory of social media heroes.

A democratic and egalitarian social media space that includes a diversity of voices may not be spectacular. It may not thrive on glamour and theatricality but on the mundane and ordinariness of our everyday lives. But it is the space we should strive for.

Because ultimately, heroes are ordinary.

This article republished from The Wire.