On 15 January, the Bombay High Court allowed a request by FMCG giant Marico Limited for an interim injunction against vlogger Abhijeet Bhansali, requiring him to take down a video in which he reviews Parachute Coconut Oil – which the company claims made disparaging remarks about their product.

“Social Media influencers, whether their audience is significant or small, impact the lives of everybody who watches their content. They do have a responsibility to ensure what they are publishing is not harmful or offensive.”

Bombay High Court in Marico vs Abhijeet Bhansali

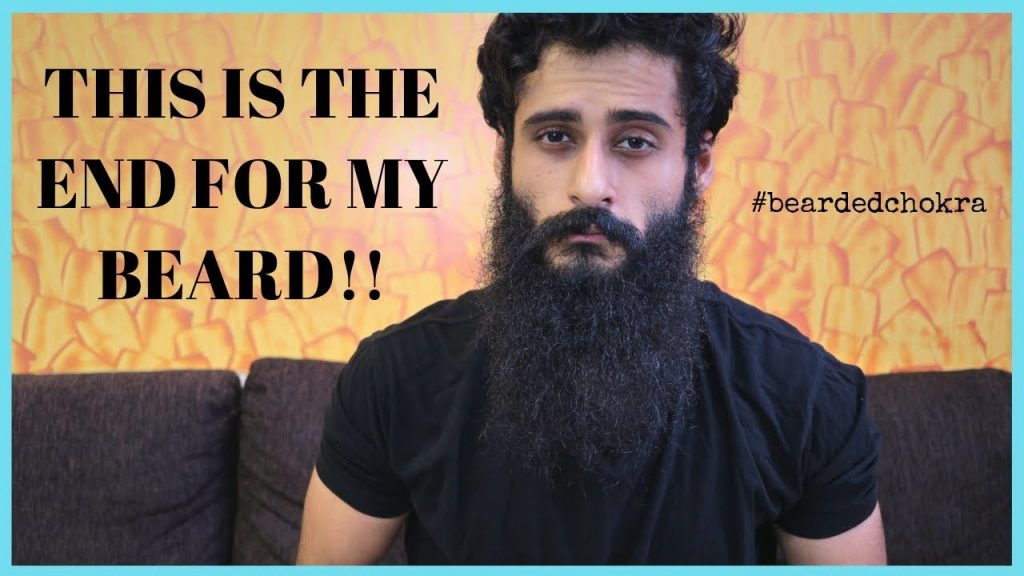

The order is not a final decision on the main case under the tort of disparagement, but is an interim relief for Marico, which argued that allowing this video by Bhansali – who runs the YouTube channel ‘Bearded Chokra’ which has 152 thousand subscribers – to stay online was causing them irreparable damage, and thus, needed to be taken down at least till the time the court decides the main case.

Nevertheless, the order could prove to be a very significant one in the times to come thanks to its recognition of the recent rise of ‘social media influencers’ – and its subsequent warning to them to be more responsible.

What Was This Case About?

To get an interim injunction in a case like this, the party requesting it has to show that there is a prima facie case to show that the other party has done them some wrong, that not passing the injunction would cause irreparable injury, and that on balance, they will suffer more than the other party if the injunction is not granted than the other party if it is actually granted.

To satisfy the first part of this test, Marico therefore had to demonstrate to Justice SJ Kathawalla that they had a prima facie case of disparagement:

- That Bhansali had made false statements in his video about Parachute Coconut Oil;

- That the statements were made by him either maliciously or recklessly; and

- That the video caused ‘special damages’ to Marico.

What Do Social Media Influencers Have to Do With This Case?

It was in terms of the latter two elements – recklessness and special damages – that Bhansali’s status as a social media influencer came into play.

The order defines social media influencers as individuals who have acquired a considerable follower base on social media along with some amount of credibility when it comes to the space in which they operate.

According to the judge, these influencers often “employ the goodwill they enjoy amongst their followers/viewers to promote a brand, support a cause or persuade them to do or omit doing an act.”

They could even, Justice Kathawalla noted, use their influence to dissuade followers from purchasing certain products – as Bhansali had done in the video in question when he suggested that people should not buy Parachute Coconut Oil.

As a result, he noted, social media influencers like Bhansali have “the power to influence the public mind.” The judge held that this meant they can make statements with the “same impunity available to an ordinary person.”

Essentially, what the judge was saying was that if a regular person makes statements in a video or elsewhere which may not be entirely accurate, this is less likely to to cause damage to a company or its product’s reputation, than when an influencer does the same thing. The reach and popularity of a social media influencer means they have a greater responsibility to ensure that their statements don’t mislead the public or provide incorrect information.

“Such person bears a higher burden to ensure there is a degree of truthfulness in his statements. A social media influencer is not only aware of the impact of his statement but also makes a purposeful attempt to spread his opinion to society/the public.”

Bombay High Court in Marico vs Abhijeet Bhansali

Special Damage

‘Special damage’ in tort law has nothing to do with the value of loss caused to a person, but whether there is some form of irreparable loss to them in terms of reputation.

When looking at whether or not Bhansali had caused special damage to Marico and Parachute, the judge noted the 1,08,000 views, the 2,500 or so ‘likes’ and several comments by viewers, including comments saying they would no longer use Parachute, and that they would share the video with others.

The nature of the comments and the numbers here were sufficient according to the judge to show that there was damage to their reputation.

While Justice Kathawalla didn’t expressly refer to Bhansali as a social media influencer in this part of the order, if this is how a court will assess special damage, influencers are likely to be more vulnerable, as their large subscriber/follower count will mean more views, and will also mean more people are likely to agree with their opinion and trust it.

Does This Create a Problem for Influencers, Going Forward?

The judge’s views on social media influencers throughout the judgment were not merely observations. Some of these, particularly on the issue of recklessness, were meant to be findings and so can be cited in subsequent cases as well as by angry companies looking to get an unflattering review taken down.

Now, this should not mean that any social media influencer who puts out a negative opinion about a product is going to be facing lawsuits from an irate manufacturer. The judge arrived at the finding of recklessness after reviewing the arguments about the accuracy of Bhansali’s statements and the way in which he put them forward, and it was because of Bhansali’s failings in these departments that he was found to have been reckless.

He had claimed that he had done his research on various oils and how to assess which ones were better, he claimed to have done an “extensive review of the Parachute Coconut Oil with the tests and proof” and he used forceful and assertive language like “I will prove it”, “bring the truth to you”, etc. After assessing the claims made by Bhansali in his video and the research he’d relied on for this, the court found that this wasn’t up to the mark.

It’s in circumstances like this that social media influencers will have to be particularly careful, as intellectual property lawyer Eashan Ghosh explains:

“This is a controversial but important warning to influencers: if your content about a product or service conveys an impression that it is based on research, courts will probe into whether the research reasonably supports the content. Not just that, you will have to withstand efforts by the commercial entity that puts the product or service on the market to discredit your research.”

Property Lawyer Eashan Ghosh

If the language used by an influencer is more careful, if they don’t claim to have done extensive research or have some special expertise on the subject, then they could avoid the pitfalls that this order creates for them. Another thing to watch out for is to not go after one product only, and then recommend and include links to competing products in their content, something which proved a problem for Bhansali.

This may not be quite so easy as it may seem, since many influencers, Bhansali included, may not have even realised what they were doing was risky.

“With the advent of the internet, the youth is exposed to content from foreign social media influencers that may be considered proper as per the laws of their country,” says Ryan Wilson, an advocate specialising in intellectual property law, adding: “When they mimic such vlogging styles in India, they do so not so much with malice, but because they think there is nothing wrong with it.”

As Wilson points out, this is not something which will exonerate them in court – which means they should look to spread awareness about this kind of tort liability beyond the legal fraternity.

But was the approach of the Bombay High Court correct? Ghosh is of the opinion that the test adopted by the court to assess whether or not Bhansali had been reckless was not entirely fair.

“It’s one thing to say ‘you have a duty to post responsible content on social media’,” he argues, “it’s quite another to say ‘you have a duty to post responsible content supported by research that can stand heavy judicial scrutiny about specific products or services on social media because their owners will bring legal action against you if you don’t.”

As Justice Kathawalla acknowledges at the start of the order, the expansion and commercialisation of the internet has led and will continue to lead to new kinds of legal disputes, which the old principles and precedents may not be sufficient to cover.

Other high courts and the Supreme Court may take a different view from the Bombay High Court in other such cases – which will surely happen with the continued rise in prominence of influencers. Till then though, it might be wise for them to read up on this order, and be aware of the responsibilities that the judiciary at this time views them to have.

This article was originally published in The Quint