With over 60 confirmed cases of coronavirus currently in India and over 110K cases worldwide, the epidemic has well and truly taken over news cycles all over the world. And an equally tragic side-effect of the outbreak is the spread of fake news online. From WhatsApp forwards to tweets claiming to cure coronavirus and Facebook posts about home remedies — fake news and misinformation about coronavirus is still a big part of social media despite so-called steps taken by these platforms.

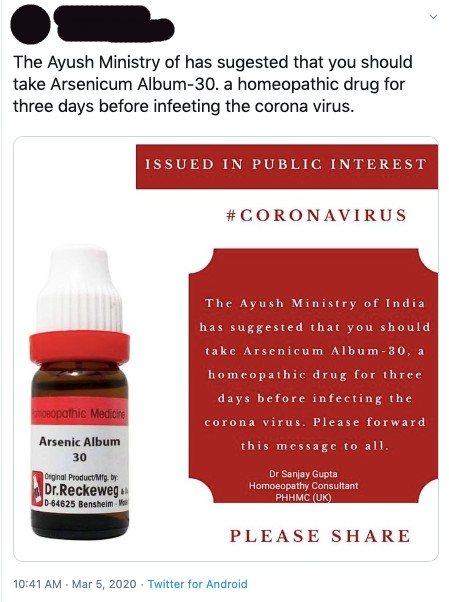

In India, Twitter timelines and WhatsApp forwards are chock-full of claims that coronavirus can be treated by homoeopathic drugs promoted by the ministry of AYUSH (Ayurveda, yoga & naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa Rigpa and homoeopathy).

In January, the ministry released a public advisory claiming that homoeopathic drugs can be used for the prevention of infection. However, it was later confirmed as false news by the fact-checking website AltNews. There are no vaccines available to cure coronavirus infection, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

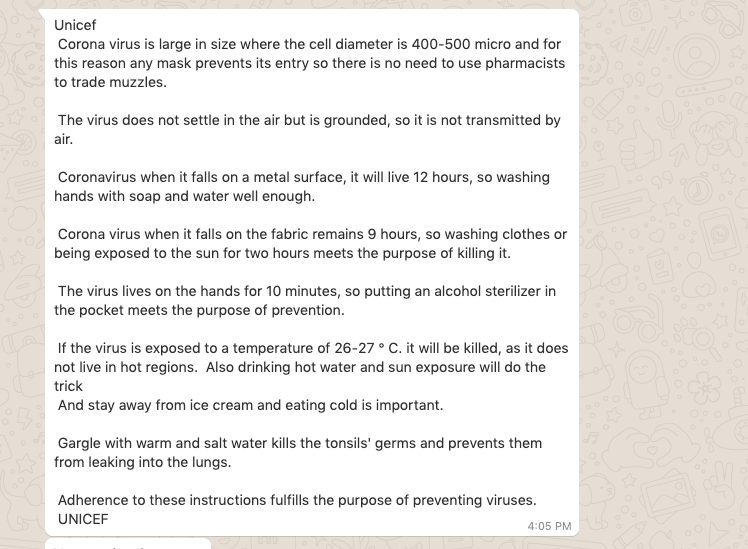

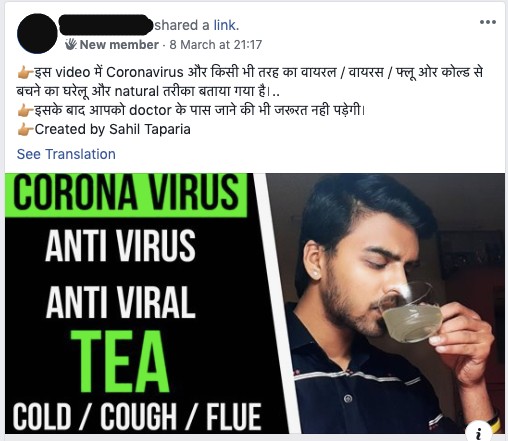

In addition to this, social media platforms also have videos promoting cow dung and cow urine as a cure for coronavirus, which has been propagated as gospel for the Hindi heartland. Many such claims of home-made remedies supposedly meant to cure coronavirus are rampant across social media platforms. We found plenty of examples of Twitter and Facebook, which violate the so-called policies in place to stop the spread of misinformation, but these posts have not been taken down.

Social Media’s Efforts To Curb Fake News

In response to the coronavirus misinformation spree, internet giants including Facebook, Twitter, Google and YouTube had pledged to work with WHO and third-party fact-checking platforms to regulate online content and fish out fake news and misinformation regarding the coronavirus.

Twitter launched a search prompt for India in collaboration with the ministry of health and family welfare and the World Health Organisation (WHO). This will mean that all Twitter searches for coronavirus or any related terms, will be shown flash links to WHO’s website.

Google, Facebook, and YouTube will also be following the same process. The step will ensure that users are getting their information from more reliable sources. Facebook’s third-party fact-checkers are also reported to have started removing content with claims that have been debunked by WHO and local health authorities. Chinese short video app TikTok too started asking its users to verify facts about coronavirus with trusted sources, by flashing warnings in eight Indian languages. Moreover, the platform is also asking its users to report any content that violates TikTik’s community guidelines.

But how effective are these measures? Beyond searches, links and articles claiming to cure coronavirus have become very commonplace in India. Last week, an Ola driver sent us a video in response to questions about the steps being taken by the company to promote awareness about the infection and the disease. The video showed a religious leader providing home remedies and cures to the coronavirus infection. Such videos are being forwarded with glee by unsuspecting users.

As schools and offices shut down, all international and national business events are being cancelled, there is an obvious panic around the spread of coronavirus, which is being exploited by those looking to capitalise on the panic. In times of such pandemics, the impact of people believing each and every piece of information found online can have severe consequences. For example, the panic has resulted in a shortage of face masks and hand sanitisers — both of which are less than ideal in the fight against the epidemic

This also raises the question of intermediary liability — should social media companies be held responsible for the spread of false information or does the buck stop with the users?

The Indian government had proposed a draft of IT intermediary guidelines of December 2018. Under which, it proposed social media sites to remove any “illegal” content within 24 hours, upon being notified by court order or a government agency.

This article republished from Inc42